Dr Justyna Nawrocka and mgr inż. Urszula Świercz-Pietrasiak from the Department of Plant Physiology and Biochemistry at the Faculty of Biology and Environmental Protection have been working on solving this problem for a year. The research results are very promising and were included in a scientific project entitled: "Wykorzystanie kompleksowego systemu bioremediacyjnego w ekologicznej gospodarce odpadami poprodukcyjnymi, wytwarzanymi w wyniku procesu produkcji komponentów artykułu spożywczego – kawioru molekularnego” [The use of a comprehensive bioremediation system in the ecological management of post-production waste generated as a result of the production process of food components – molecular caviar], as part of the Innovation Incubator 4.0 programme, implemented in the cooperation with the Technology Transfer Office of the University of Lodz. Sounds complicated? Yes, but the idea itself is simple.

The production of "molecular caviar", but also other confectionery products: jelly candies or jellies, creates waste that is difficult to get rid of because it contains thickeners, emulsifiers and gelling substances. There is little waste during the production of sweets, but it is very difficult to deal with it, which increases disposal costs. It should be remembered that gelling substances have a wide range of applications in the food industry as well as in other industries, including the pharmaceutical industry

– explains Dr Justyna Nawrocka.

It is not surprising that one of the Polish companies producing sweets, including the above-mentioned "caviar", asked scientists from the Faculty of Biology and Environmental Protection to use waste in an unconventional way.

Waste from the confectionery industry, if well secured, is clean enough to be used for other purposes. Waste components, including gums and polysaccharides, if properly decomposed, become a great material for the growth of both plants and microorganisms

– says mgr inż. Urszula Świercz-Pietrasiak.

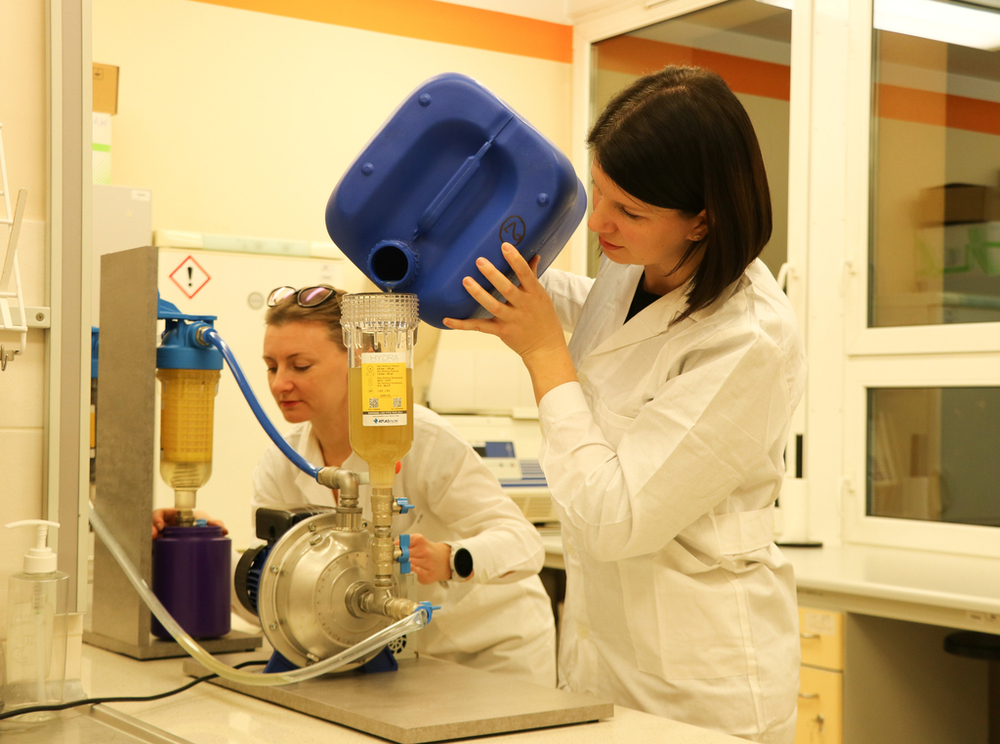

Dr Justyna Nawrocka and mgr inż. Urszula Świercz-Pietrasiak from the Department of Plant Physiology and Biochemistry with the prototype of a self-constructed, vacuum flow system for pre-treatment of liquid waste

This is where the idea of using post-production waste in a closed-loop economy came from, especially since post-production residues are non-toxic and do not contain antibiotics, heavy metals or other hazardous substances. – In order for waste to become fertiliser, it must be skilfully processed – adds Dr Justyna Nawrocka.

– In our research, we try to think in two ways – adds mgr inż. Urszula Świercz-Pietrasiak. – Firstly, we want to clean the waste so that post-production water can be reused in the company, and secondly, we want to manage some of this waste as a bioproduct or biosubstrate for plant nutrition.

In the research, carried out in accordance with the project assumptions, pre-cleaned and filtered waste was added to the substrates on which seeds were sown.

It turned out that on infertile, sandy and highly permeable soils, some fractions of the waste resulted in an increase in plant biodiversity

– says Dr Nawrocka.

The research was carried out in various experimental systems. Plant seeds began to germinate in the substrate enriched this way, while they did not germinate in substrates not containing this component. – We assume that the component will also work well in drought areas – adds mgr inż. Świercz-Pietrasiak. – Pre-cleaned and filtered waste thickens the soil and retains moisture better.

Doesn't the substance therefore pollute the soil? – No, provided the waste is properly cleaned – explains Dr Nawrocka.

What's next? – Taking into account the potential of this component, a large area of its applications opens up. There is a possibility of expanding further research in cooperation with foreign partners. The company we cooperate with is very interested in the research results, and we hope that this solution will be so universal that other companies around the world will be able to use it – adds mgr inż. Świercz-Pietrasiak.

The research has been going on for a year, and to properly understand the effect of the component on plants, we need 3-5 years, i.e. at least three growing seasons. – We also plan to check how the product will work on "tired soil", i.e. post-industrial polluted soil – adds Dr Nawrocka. – We hope to demonstrate that once the component is added, the earth begins to recover.

Dr Justyna Nawrocka and mgr inż. Urszula Świercz-Pietrasiak from the Department of Plant Physiology and Biochemistry with the prototype of a self-constructed, vacuum flow system for pre-treatment of liquid waste

Source: Faculty of Biology and Environmental Protection, University of Lodz

Text: Justyna Kowalewska (3PR)

Photographs: Patrycja Nawrocka